The project came to life over the course of two months. We had a couple of studio sessions with three creative and extremely supportive people who shared my vision. You might be surprised to hear that it involved only three people. It turned out they are real shapeshifters, able to bring to life a variety of characters – hence they made it possible. I feel truly blessed to have worked with incredibly talented Sarah Borthwick, who brought to life five of the characters featured here and played a supporting role in a sixth.

I used various techniques, such as long and multiple exposures, on-camera Cokin filters, and some post-production work to give the images their final form. That was the technical side. The main theme of the project was inspired by one of my dearest stories – One Hundred Years of Solitude. I allowed myself to add some fictional characters who did not exist in the original book, and to give them backstories that supported the images.

As you know, Anselmo Rey de la Niebla (The King of the Mist) has not been featured in Márquez’s universe, but in my view he could have been. Thus, he appears in my story, along with other whimsical characters populating the streets of Macondo.

Portraits for No One

In the last years before the wind erased the town, a solitary photographer carried in his head the faces of strangers, each dressed in the splendour of their own solitude, and though he never raised his camera, Macondo remembered them as if the portraits had always existed.

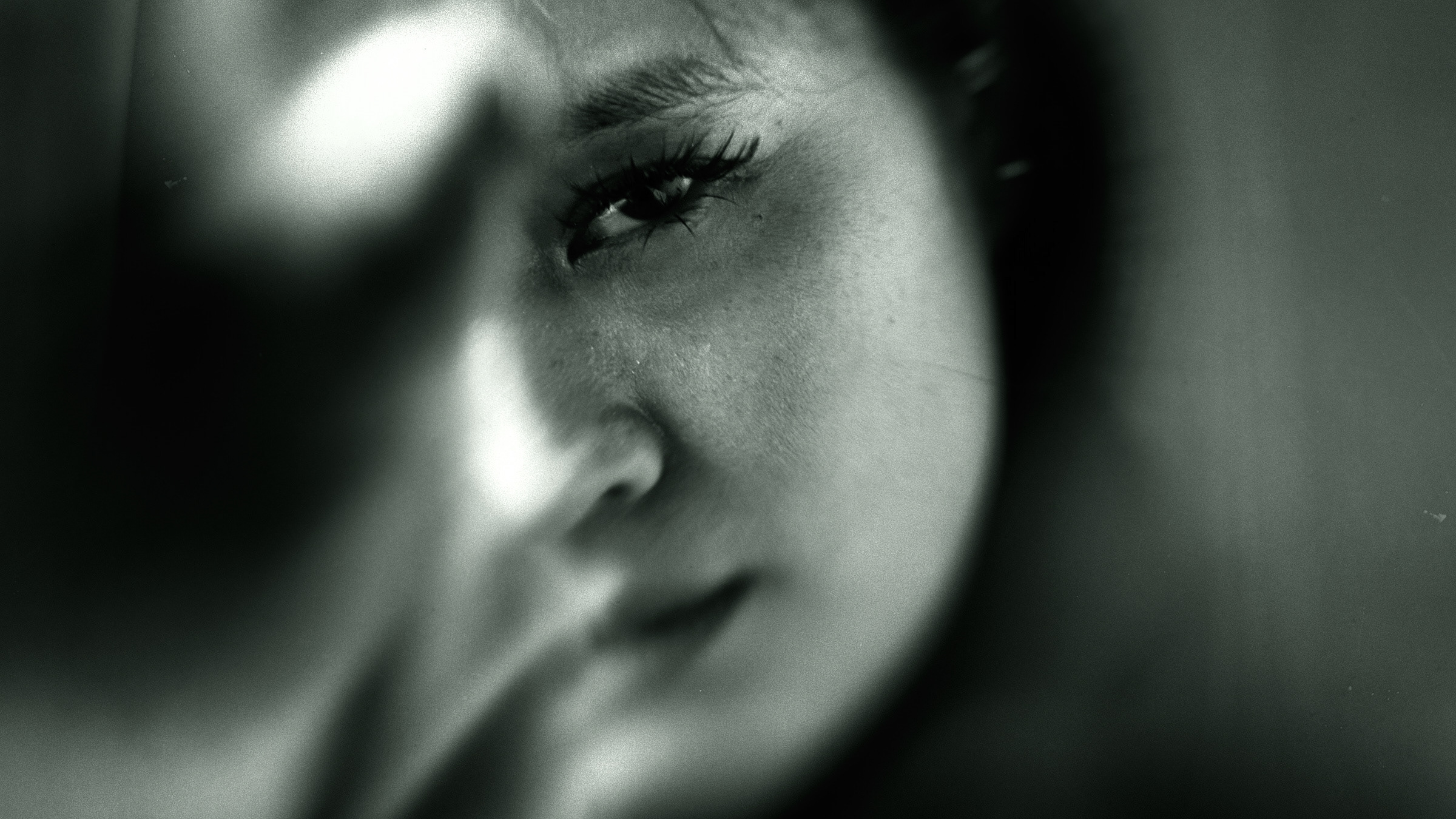

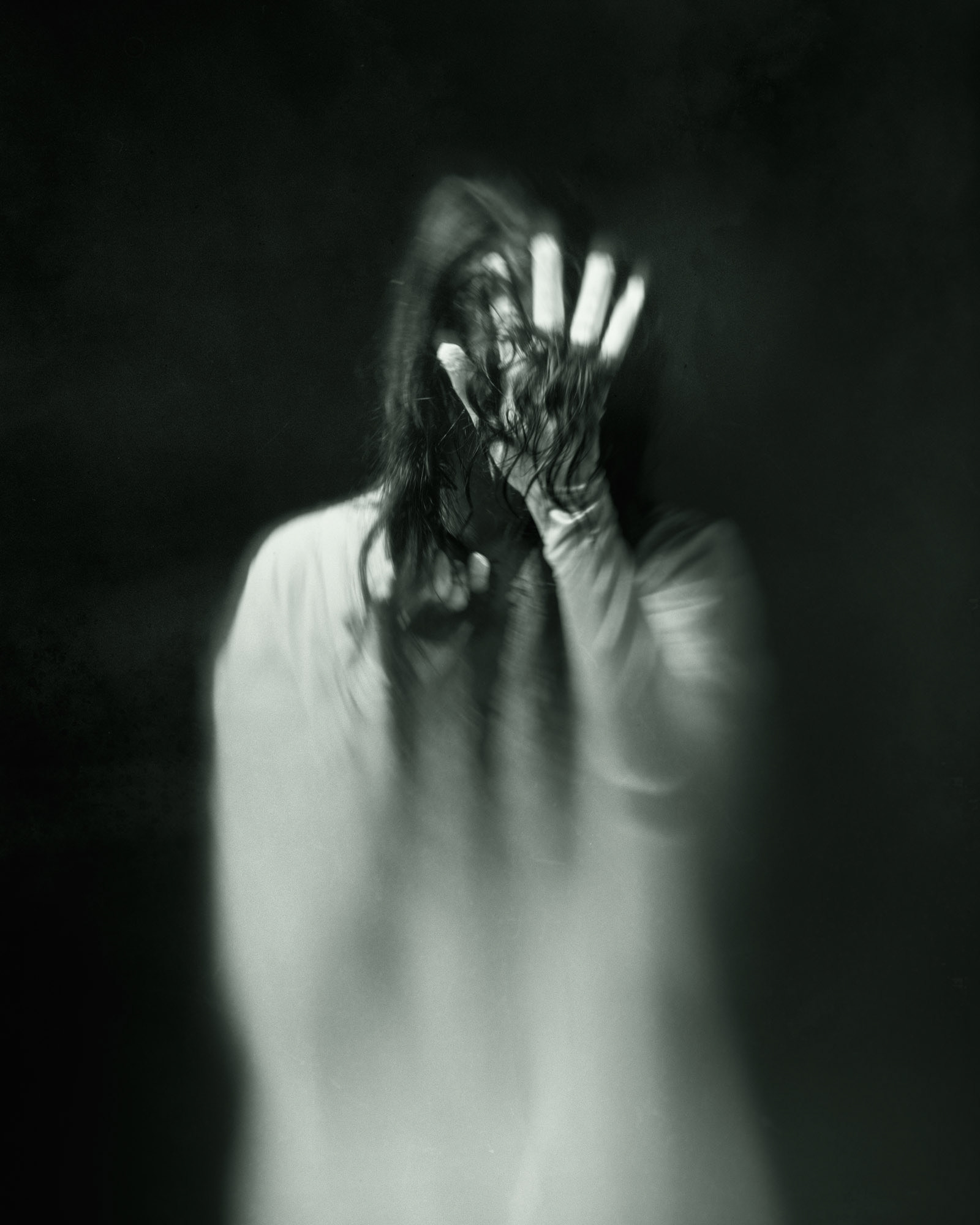

Jacinta Flor de Loto

Anselmo first saw her on a wet afternoon, barefoot in the plaza, singing to no one and to everyone at once. He did not raise his camera; he was afraid the lens would trap the rain before it could reach her hair. In his mind, she would always be lit from the side, as if the sun were peeking between two clouds just for her.

She arrived in Macondo one rainy season, barefoot and carrying a guitar wrapped in oilcloth. No one knew from which road she came. Some said she had crossed the swamp barefoot, guided only by the fireflies; others swore she floated down the river on a raft of bougainvillea. She lived in a room above the abandoned telegraph office, where she painted the walls with suns and moons and taught children songs that no one could remember the next morning.

Jacinta dressed in skirts dyed with marigolds and smoked hand-rolled cigarettes that smelled faintly of cinnamon. She sang at dusk, when the wind carried her voice all the way to the banana fields, and her songs made the workers pause in mid-swing, as if listening for some long-forgotten promise.

Her solitude was not the absence of people, but the inability to find anyone who could hear the exact music she carried inside her. She wrote letters to a man she had never met, sealed with petals, and left them in the hollow of the oldest almond tree, confident the wind would deliver them.

In the end, she was last seen walking towards the horizon on the day the rain began to fall and did not stop for four years, eleven months, and two days. The children claimed they saw her vanish into the curtain of water, still singing, her hair heavy with the scent of wet jasmine.

Weeks later, as the rain slowed, he smelt sugar and rum drifting from the boarding-house kitchen. Through the half-open door he saw Eusebio, sleeves rolled, his hands dusted in flour, bent over a cake like a priest before an altar. The photograph in his mind was so complete he feared to take it, as if the act might cause the cake to vanish.

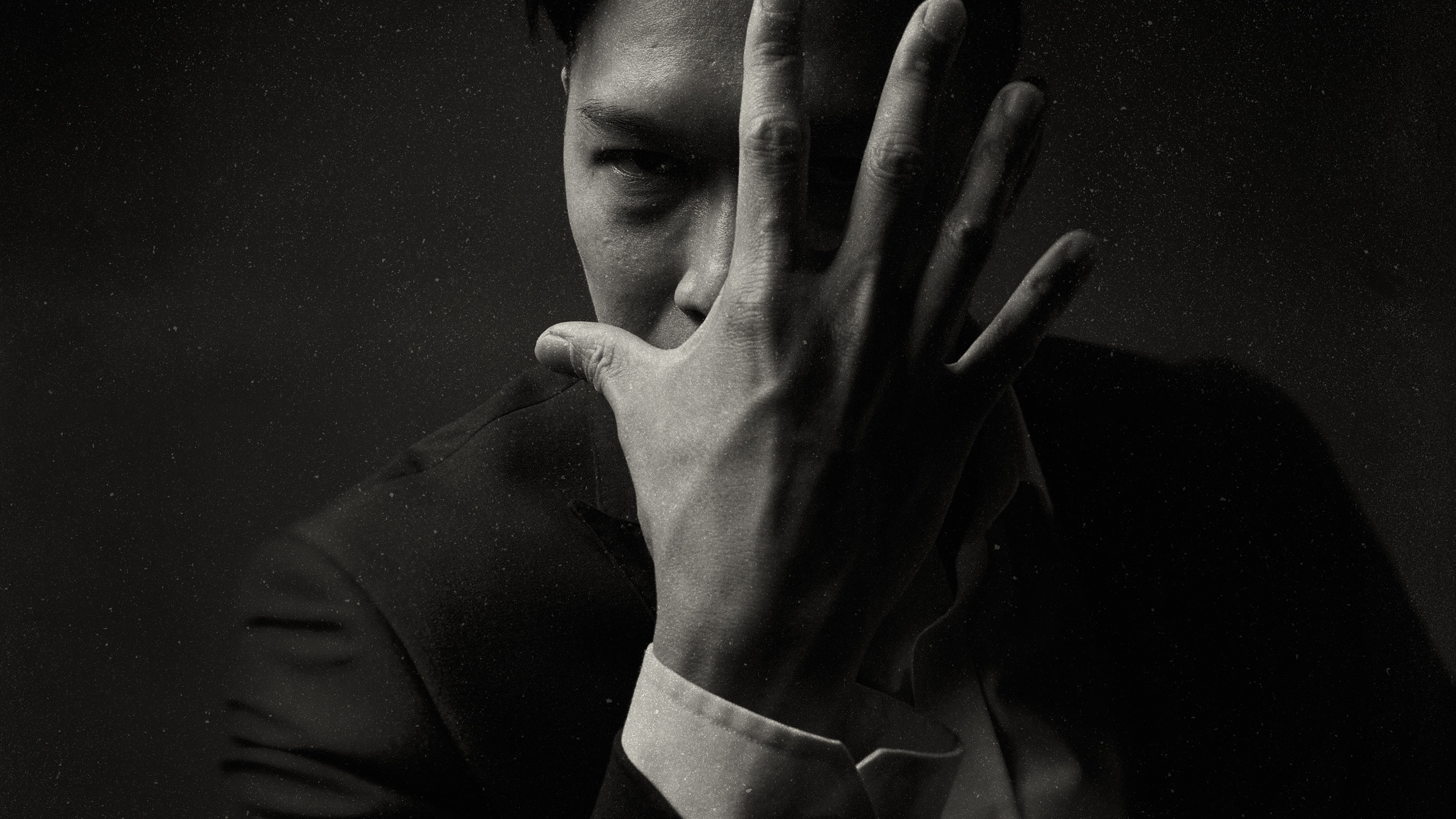

Eusebio Blanco de la O

Eusebio was born with the hands of a master baker and the temperament of a saint. His earliest memory was of his grandmother lifting him up so he could see inside the oven, the cake rising like a small sun in the dark. From that day on, the smell of vanilla was his secret compass.

But his father, who trusted numbers more than butter, told him that flour was a gamble and sugar a vice. So Eusebio became an accountant, burying his talent beneath neat columns of figures. He wore white linen suits so immaculate they seemed untouched by life, his broad frame giving him the look of a man who could carry anything, except his own longing.

At night, he would bake in secret: perfect sponge cakes, airy as afternoon clouds; dense fruitcakes soaked in rum until they smelt like remembered holidays; tarts glazed so finely they reflected candlelight like shallow ponds. He never ate them. He never served them. He arranged them on his kitchen table, admired them in silence, and then, before dawn, carried them into the banana fields, leaving them in the shade of trees like offerings to an unacknowledged god.

The townspeople occasionally found these cakes and whispered about them, as if they had appeared by magic. Some swore they were meant for the dead; others claimed they were traps to lure lovers back to a sweetness they had forgotten.

Eusebio baked for decades, his love of cake swelling inside him like a secret rising under the heat of its own devotion. And one morning, after the winds began to gather at the edges of Macondo, he was seen wheeling a cart piled high with wedding cakes, each one crowned with a tiny sugar bride and groom. No one knew who they were for.

Luciano del Amanecer

On market day, the crowd parted for a figure in a scarlet pelisse, the gold braid shining like a prize. Anselmo imagined the soldier framed against the sky, one hand on the hilt, the other hiding the tremour of someone who could not bear to do harm. He adjusted the focus in his mind until the uniform and the soul beneath it were in equal clarity.

When Lucinda first put on the scarlet pelisse, she thought it was a garment meant to honour her beauty. The gold braid framed her shoulders like rays from a saint’s halo; the fur collar brushed against her cheek with the tenderness of a lover’s hand. In the mirror, the uniform did not disguise her feminine soul; it adorned it, made it luminous.

But the uniform was not a costume. It was a contract. Along with the gleam of polished boots came orders: to stand in front of unarmed villagers with a rifle; to drag men from their homes in the name of stability; to watch without intervening as punishment was carried out. The pelisse that had once felt like a crown began to weigh like a chain.

She obeyed at first because she believed obedience was survival. Yet each act demanded by the uniform left a mark inside her, invisible at first, then slowly visible in the mirror as a tightening around the mouth, a shadow behind the eyes. The beauty the uniform once celebrated began to curdle into something brittle and sour.

Luciano, as some knew her, became a man not by birth but by the slow erosion of gentleness. The very garment meant to elevate her spirit instead calloused it, until even the scent of its wool seemed soaked with cruelty she had never wanted to own.

Still, she kept it immaculate. Every morning she brushed the dust from the braid, polished the buttons until they caught the sun. Outwardly, she was the perfect soldier: poised, symmetrical, untouchable. Inwardly, she mourned the soft self she had been before the first order was given.

Her solitude was the gulf between what the uniform showed and what it demanded, the unbearable knowledge that she could be admired for the same image that was slowly unmaking her.

One morning, she folded the pelisse carefully, as if returning it to the person she had been when she first wore it, and left it on the steps of the railway station. She walked away in plain clothes, her black hair unbound, carrying nothing but the hope that without the uniform, her soul might learn softness again.

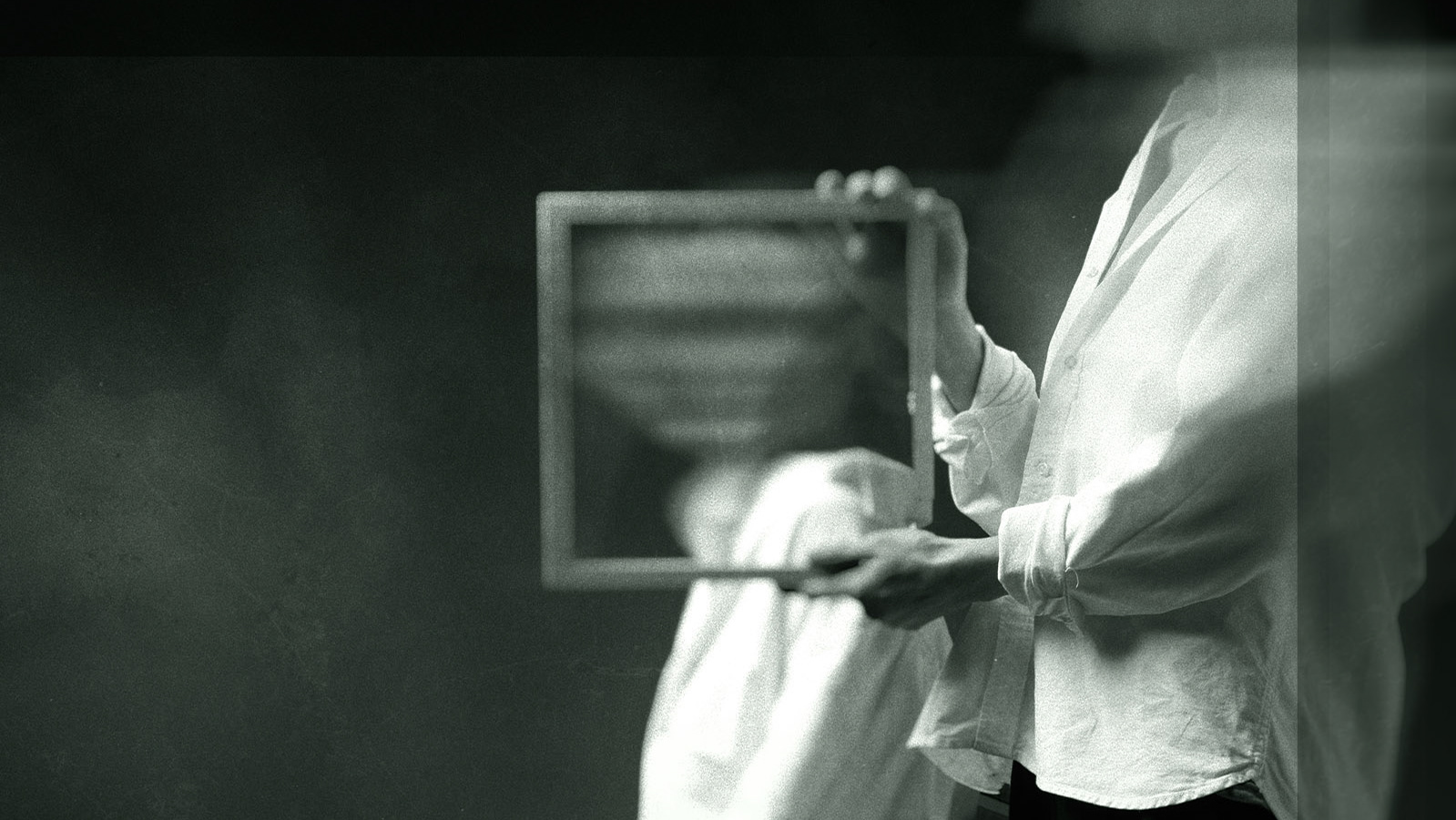

Adelina Sueños

On the following market day, Anselmo saw her sitting beneath the almond tree, her cedar box balanced on her knees. She spoke quietly to a man who shifted from foot to foot, then passed him a small envelope sealed with beeswax. The photograph in his mind was all stillness, the slight bend of her head, the glint of wax, the hush of a promise that would follow the man home and wait for him in the dark.

Adelina arrived in Macondo carrying a cedar box and an unusual promise: for a modest fee, she would compose a dream especially for you. Not interpret one you’d already had, nor predict one yet to come, but fashion a dream from scratch, tailored to your heart as precisely as a fine dressmaker might cut cloth.

Before she began, she always asked the same three questions: What do you fear most? What have you never confessed? What do you hope to see before you die? Her customers quickly discovered that their answers determined the tenor of the dream. Those who answered truthfully awoke from nights scented with jasmine and salt air, having walked through gardens where the departed waited to greet them, or sailed on seas that murmured their secrets back in their own voices.

Those who lied were not so fortunate. Their dreams led them into wedding feasts where the groom never appeared, banquets where every mouthful turned to ash, or streets where the faces of friends and neighbours were as blank as uncarved masks.

She wrote each dream on a thin slip of rice paper, folded into a small envelope sealed with beeswax. She instructed her customers to slip it beneath their pillow and leave it unopened. By morning, the paper would be gone, absorbed into the sleeper’s breath, and the dream would have paid its visit.

Some became dependent on her, visiting week after week until they could no longer tell waking life from the world she had made for them. Others came only once, finding a single dream, beautiful or terrible, enough to alter the course of their days.

Adelina never wrote a dream for herself. “I can’t answer the three questions honestly,” she would say with a small smile. One evening, as the wind began to rise at the edge of town, she was seen burning a pile of sealed envelopes in the plaza. The smoke smelt faintly of lavender and salt. By the next morning she had gone, leaving the cedar box behind. Inside were three slips of paper, each bearing a single word: Fear. Confession. Hope.

He never asked her to write a dream for him. Instead, he stored her in his private album, a profile in half-light, as if she were one of her own creations and might vanish if he stared too long. That same week, passing the church at dusk, he noticed a bride in white standing alone before the altar, as if awaiting a signal only she would recognise.

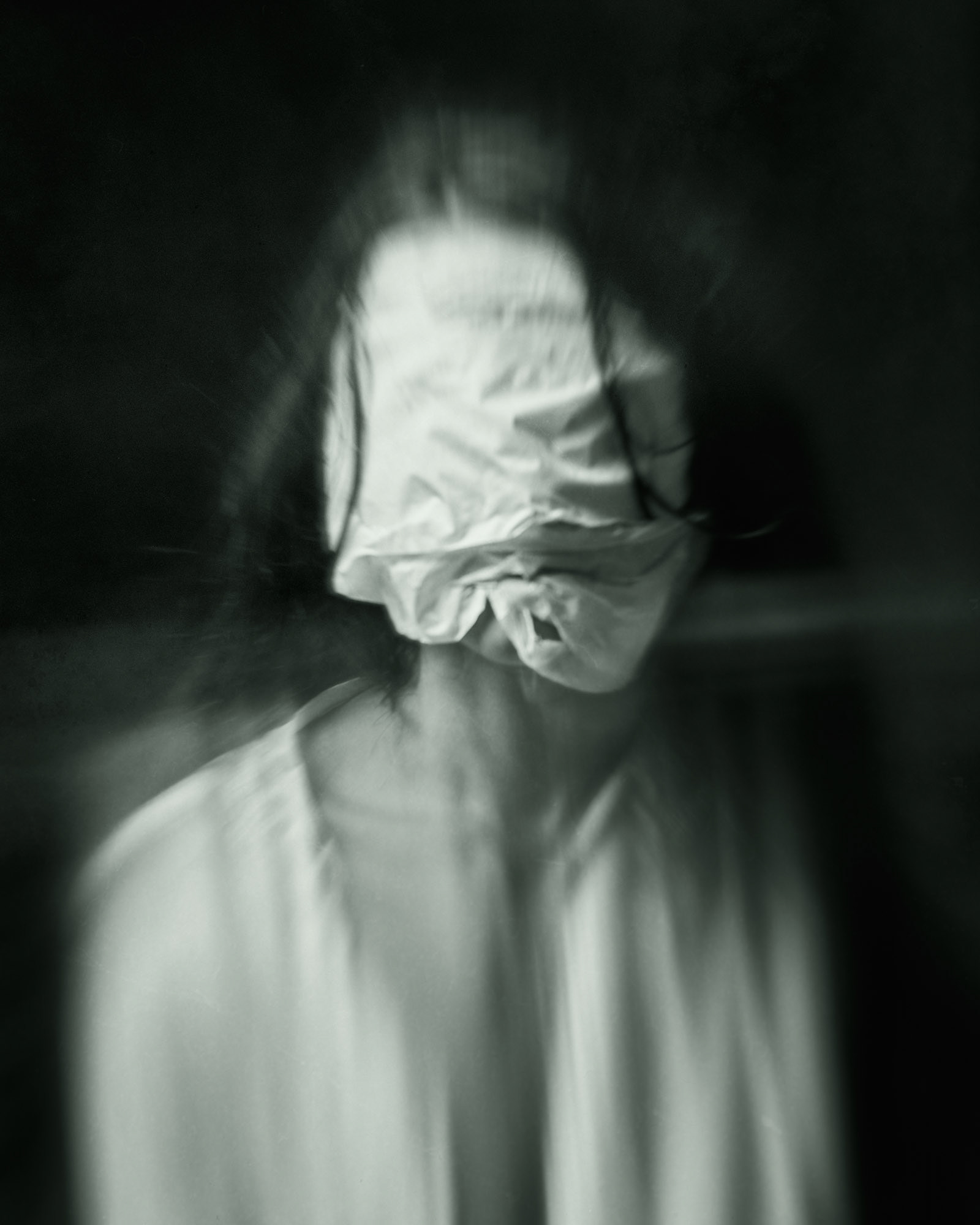

Isabel de los Votos

From childhood, Isabel wore white. Not because of fashion or poverty, but because she considered herself permanently in rehearsal for her wedding day. She embroidered her own trousseau before she turned twelve, filling cedar chests with lace and lavender sachets. By her sixteenth birthday, she had memorised the church’s wedding mass by heart and practised walking down the aisle in the dim corridors of her house, the hem of her dress sweeping the dust like a broom.

But beneath her devotion to the idea of marriage, there was a vow even stronger: she would die a virgin. This contradiction was the architecture of her soul. She wanted the love, the celebration, the veil, but she wanted to keep her untouched body as her final act of autonomy, the one thing in her life she could control in a world that decided everything else for her.

Suitors came and went like seasons. She entertained their proposals, took their photographs, even sewed her initials into imaginary linens. But at the moment when courtship threatened to become engagement, she would vanish, sometimes for days, sometimes for months, returning with a calm smile and no explanation.

Over the years, Isabel’s beauty grew spectral, as if she were becoming the ghost of her own wedding portrait. The townspeople began to see her in their dreams, standing at the church door with a bouquet of white carnations that never wilted. The bells would ring, but she never crossed the threshold.

In her final days, the wind had already begun its long moan through Macondo’s streets. Isabel was found in her bedroom, wearing her wedding dress, her hands folded over a prayer-book. No one could say if she had been waiting for the groom or for death, or if, to her, they were the same thing.

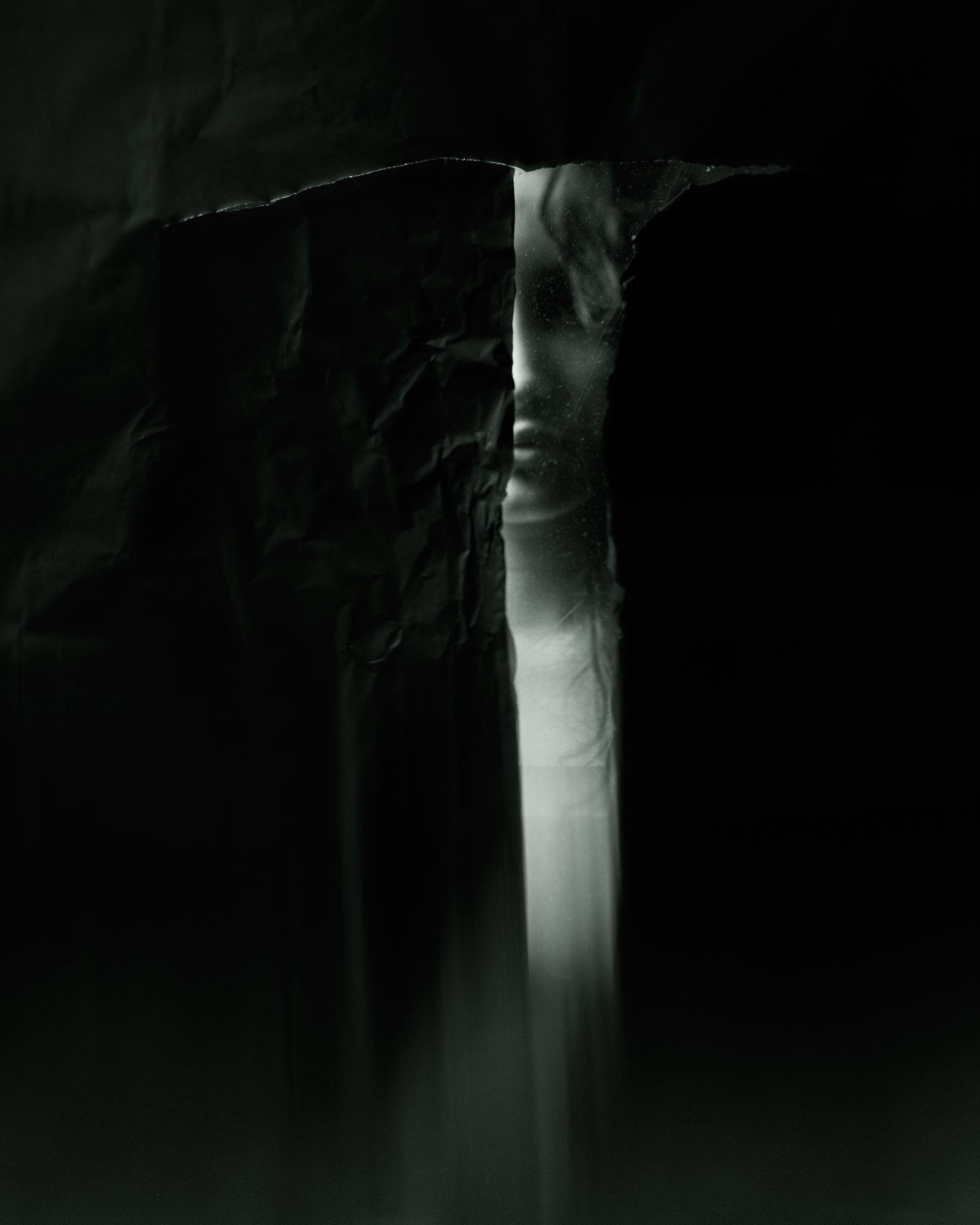

Doña Remedios del Silencio

Days later, passing the almond tree, he saw the half-closed shutters and the stillness of a woman who had been there all afternoon. In his mind, he caught the exact moment before her lips curved, knowing the photograph would live for ever in that half-smile, never reaching its end.

No one in Macondo could remember the day Doña Remedios arrived, though they all claimed to have seen her before. She lived in the upper room of the old house across from the almond tree, where the shutters were always half-closed, letting in just enough light to illuminate her face without ever revealing it entirely.

Her beauty was not the kind that startled, but the kind that lingered, an expression balanced perfectly between sorrow and amusement, as though she knew both the tragedy and the punchline of the same secret. She was rarely seen speaking, and when she did, her words were so measured that the listener could never be sure if she was answering a question or asking one.

Remedios spent her afternoons seated at the window, embroidering handkerchiefs she never sold or gifted. Strangers passing through town would stop and stare, convinced she was about to smile at them; locals knew better. They said her lips had been holding back the same smile for decades, as if releasing it might change the course of events in Macondo.

Some believed she had once been a great beauty courted by generals; others whispered she was the child of a mirror and a shadow, destined never to grow old. The truth was that no one could recall her ever being younger, or older, than she was now.

During the final days, when the wind began to howl at the edges of the town, Doña Remedios was seen for the first time in the plaza, standing perfectly still as if posing for a portrait that only she could see. And just as the first gust tore the awnings from the café, she smiled, not at anyone in particular, but as if at last her private joke had found its punchline.

When the wind cleared, her chair remained by the window, empty. The handkerchief in the frame was unfinished, the last stitch hanging loose like a word left unsaid.

Don Gregorio Máscaras

Anselmo noticed him in the plaza one afternoon, laying out faces on a tablecloth as if they were fine china. The salesman moved each one into the shade, avoiding the glare that could warp their features. Anselmo imagined the portrait: Gregorio leaning over his leather case, the glint of sunlight on resin, the faint reflection of the town in a pair of eyes that were not his own.

Don Gregorio arrived in Macondo with a leather suitcase so large it seemed to contain a person. Inside were dozens of faces, each resting in its own compartment like rare fruit: faces for weddings, for funerals, for seductions, for business negotiations, even one for the quiet act of forgiveness.

He claimed each face was washable and reusable, made from a resin as soft as human skin but strong enough to survive the dust storms. He demonstrated how to fix them in place with a delicate adhesive “stronger than truth itself,” as he liked to say. A shy man could become a charmer in seconds; a widow could regain the blush of her youth; a soldier could wear the look of someone who had never seen war.

Gregorio himself never removed his own face in public. In the mirror of his hotel room, he would take it off and polish it, revealing another face beneath, paler, thinner, and tired in a way that seemed older than the town itself.

People bought his faces eagerly at first, but over time they noticed that wearing the wrong expression for too long made it stick. A man who wore the “Forgiving Face” for a month found he could no longer hold a grudge, even when he wanted to. A woman who kept the “Bride’s Face” for a year lost interest in her own husband but spent hours staring at herself in the mirror.

Gregorio didn’t mind. Faces, like seasons, were meant to be replaced. But one evening, as the wind began to rise on the outskirts of Macondo, he discovered that the compartment for his own face was empty. He had sold it without noticing, perhaps in exchange for a night’s lodging or a loaf of bread.

He left the town before dawn, wearing no face at all, and those who saw him said it was like looking at smoke, something you could see and not see at the same time.

When Anselmo learned the salesman had left without his own face, he imagined the photograph as nothing but a dark oval where the features should be, a picture that could be anyone, and so became no one. He carried it with the others, in the same album that would never be printed.

Anselmo Rey de la Niebla

Anselmo was Macondo’s only photographer, though no one had ever seen him take a picture. He owned a camera so old it had once belonged to a travelling magician, its bellows patched with scraps of velvet, its brass fittings polished to a soft glow. He carried it everywhere, to the market, to the church, to the banana fields, but the lens cap never left its place.

He told himself he was waiting for the perfect moment, though secretly he feared that capturing someone’s face might steal not their soul, but his own nerve. And so his greatest portraits existed only in the darkroom of his mind.

He imagined Jacinta Flor de Loto caught mid-song, her hair spilling like jasmine-scented smoke. Eusebio Blanco de la O bending over a cake, the sugar catching the light like frost.

Lucinda, or was it Luciano? - with the gold braid of the hussar’s jacket lit as if on fire.

Isabel de los Votos in her wedding dress, eyes fixed on something only she could see.

Doña Remedios del Silencio framed by her half-open shutters, the almost-smile suspended in air.

Each of these images Anselmo carried with him, revisiting them like old friends. In the heat of midday, he would stand under the almond tree, close his eyes, and adjust the invisible aperture, refine the imaginary focus, frame the shot no one else could see.

Years passed, and the photographs in his mind grew sharper than anything silver nitrate could hold. In the season when the wind began its long lament, Anselmo was seen wandering the plaza, cradling his camera as if it were a child. “I have them all,” he whispered to no one. “Perfect. And untouched by time.”

When the wind finally swept through Macondo, his camera was found in the ruins of his house, the lens still capped. Inside the case was a single undeveloped plate. The townspeople, curious, held it up to the light, but it was perfectly blank, as if the portraits had chosen to stay in his head for ever.

Long after the wind had emptied the houses and smoothed the streets, the ruins of Macondo held no trace of the people whose lives had once bloomed there. But in the quiet that followed, when the dust settled and the sun poured over the cracked tiles, it was said that if one stood in the plaza at noon and closed their eyes, they could still see them: the singer with jasmine in her hair; the baker in his immaculate white suit; the hussar with the jet-black braid; the bride who never crossed the threshold; the woman at the window who almost smiled.

And always, somewhere at the edge of vision, the photographer, Anselmo Rey de la Niebla, standing perfectly still, his lens capped, guarding the only portraits that time could never fade. They lived only where he had placed them: in the darkness behind his eyes, untouched, unchanging, and as beautiful as the day he first imagined them.

London, August 2025